Mwizenge S. Tembo, Ph. D.

Emeritus Professor of Sociology

The traditional Tumbuka cooking of Chigwada vegetable ndiyo, dende, relish or umunani involves many stages. These were followed when I cooked the Chigwada as “The Village Chef” at the Mwizenge Sustainable Model Village with the help of two Research Assistants; Mr. Robert Phiri and Ms. Jusi Nya Banda.

Stages of Cooking Chigwada

You start with making chidulo, second collect fresh tender chigwada or cassava leaves, third pound the leaves with a pestle and mortar, fourth pour the chidulo into a cooking pot and put the mashed-up leaves into a cooking pot and place it on the fire. Boil the chigwada for half an hour and add nthendelo, nthwilo or raw fresh groundnut powder. Add salt and any tomatoes. Boil covered for half an hour. Stir every few minutes to avoid burning at the bottom. Add some water if the chigwada seems to be thickening. After half an hour, stir the nthendelo in the chikwada. After cooking for two and half hours, the Chigwada is ready to serve and eat with sima or nshima. I will critique my cooking of the Chigwada and the taste compared to how my grandmother and my mother used to cook it.

1. Chidulo is made from a choice of many dry leaves of a farm field crop. The chidulo can be made from dry maize stalks, from vitondozo vya skaba or stalks of dry groundnut leaves, dry banana leaves, dry groundnut shells, dry bean plant leaves and shells, dry visokoto from maize. In this case I decided to use the dry stalks of the maize which was about to be harvested. We set a pile of the stalks on fire and collected the cool ashes.

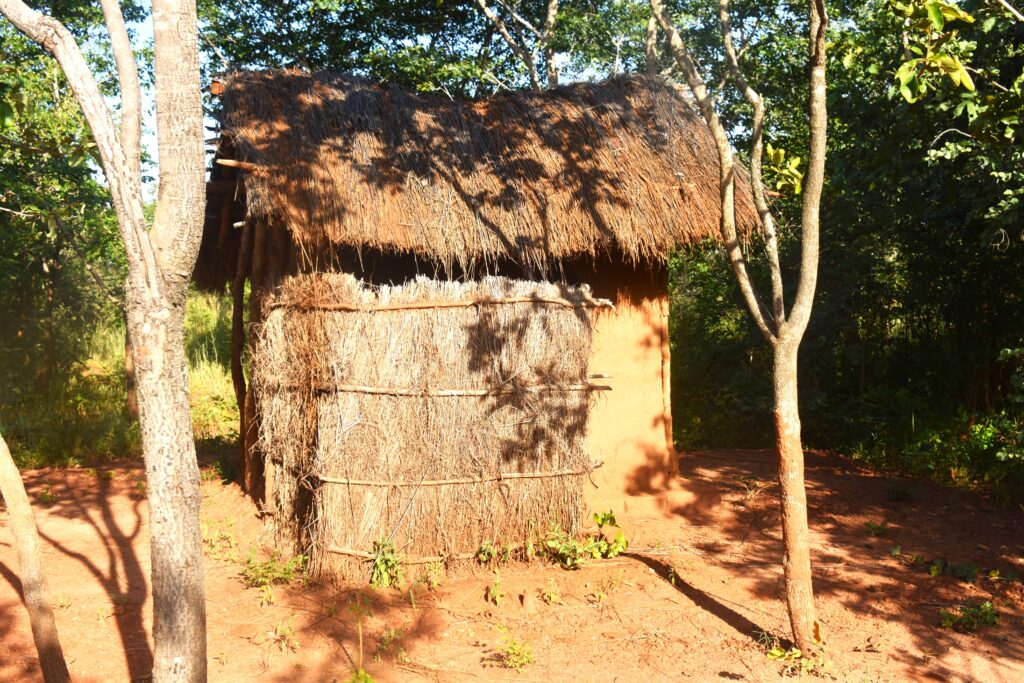

2. The ashes were put in chichezo container which had holes made at the bottom. The ashes were placed in the container and cold water was poured into the ashes. Soon, a dark golden brown liquid began to drip out at the bottom which was collecting in a container at the bottom.

3. We collected about 2 lbs or 1 Kg of fresh soft or tender chigwada leaves from the trees. Put them in a mortar and pound the leaves until they are a wet moist mash.

4. We pounded raw peanuts with a pestle and mortar and made about 6 cups of fresh peanut or groundnut powder.

5. We poured 5 cups of the chidulo liquid into the cooking pot and added the mashed chigwada leaves and began to boil the chigwada for 30 minutes.

6. I poured 4 cups of the raw groundnut or peanut powder on top of the chigwada. DO NOT stir yet. Add one teaspoon of salt. You can add tomatoes but this is optional. Boil covered for 30 minutes.

7. I stirred the chigwada vigorously and let it simmer and added water if necessary if the chigwada is drying up. Stir every few minutes to prevent the chigwada from burning at the bottom. Lower the heat.

8. After two and half hours, stir the chigwada and remove it from the fire as it is ready to be served with nshima.

Critiquing the Cooked Chigwada

I ate and enjoyed the nshima with the cooked chigwada. But the taste was nowhere close to how my grandmother and mother used to cook it. Fist I need to determine which crop stalk has the strongest chidulo. Is the chidulo from the dry groundnut leaves, banana leaves, bean leaves or maize visokoto and any other, the strongest? I could not find a flat stable surface for the sensitive scale I was using. This might sound simple. I could not find a small foldable table in Lusaka after going to so many shops.

My grandmother and my mother used a clay pot for cooking. This may make a difference. I think the chigwada needs very slow deep cooking. Metal pots are not always the best way to cook all foods. Adding more water when cooking the chigwada dilutes the chidulo which needs to have a sharp acidic taste at its best. Chidulo is not just a flavoring to the Chigwada but it is a central ingredient that tremendously defines the characteristic taste. It is a uniquely Zambian taste embedded in traditional cooking among the Tumbuka.

What was best about the cooking experiment is that we had all the basic tools. When we repeat or replicate the cooking, my team and I will only improve and get better. This is the central feature of any scientific approach.